Why global south voices are crucial in the fight against climate change

Climate change is one of the most urgent problems facing humanity today. Every country on Earth is already feeling the impacts of the warming planet, from devastating heatwaves to sweeping floods.

Wealthy nations are responsible for the lion’s share of the greenhouse gas emissions that drive global warming.

However, the poorest and most vulnerable members of society – often in the global south – bear the brunt of climate impacts. These communities are also routinely sidelined and under-represented in academic research and the media.

I am Ayesha Tandon, the science correspondent at Carbon Brief, a climate journalism and analysis website. Over the past five years, much of my work has focused on improving the representation of voices from the global south in media coverage of climate change.

Under-represented

My work on representation in climate science began in 2021, when Carbon Brief published a “special week” of articles about climate justice. As a science writer, I decided to investigate inequalities at the core of modern science – the academic publishing system.

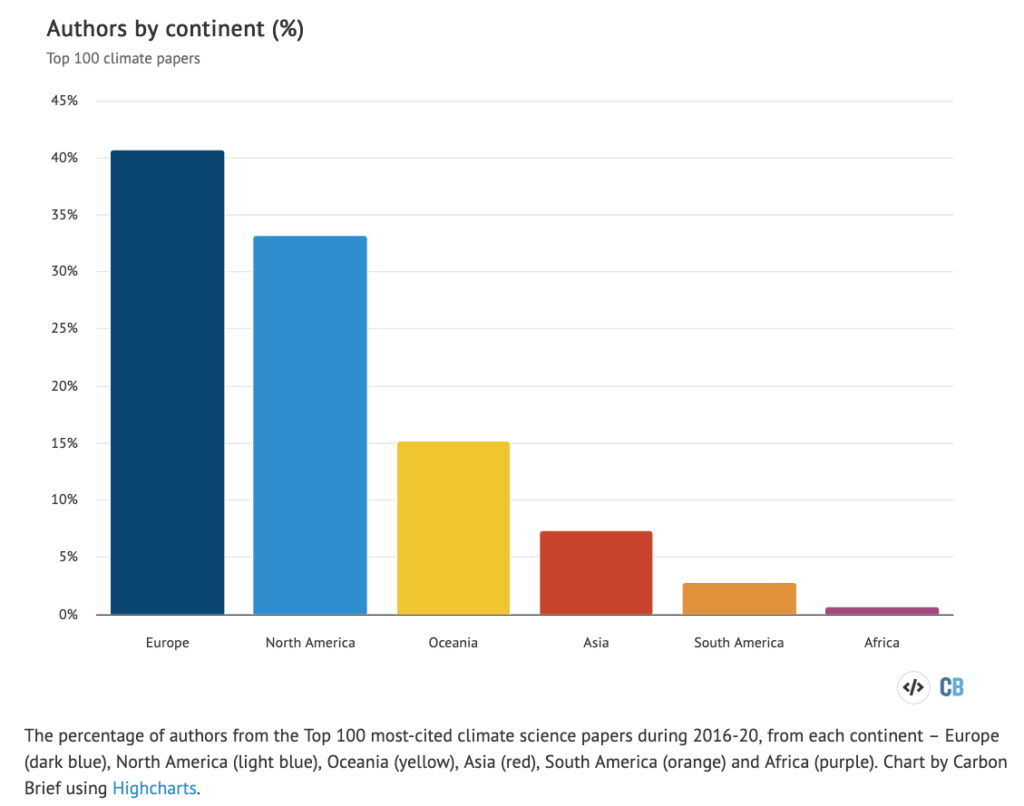

First, I identified the 100 most highly-cited academic studies about climate change published between 2016 and 2020. These papers had around 1,300 authors in total. I then recorded the country that each author’s institution is based in.

The results were unsurprising.

Almost three-quarters of the authors in my analysis were affiliated with institutions in Europe or North America.

The top-ranking countries were the US, Australia and the UK, which together accounted for more than half of all authors in this analysis (around 30%, 15% and 10%, respectively). Meanwhile, nine out of every 10 papers in my analysis included at least one researcher from the UK, the US or Australia.

Overall, around half of all researchers from the global south (defined in this article as countries in Asia, Africa and South America) were from China – which accounted for around 6% of all researchers in the analysis.

Fewer than 1% of authors in the analysis were based in Africa.

Barriers

To dig into the reasons behind this stark imbalance, I spent hours talking to scientists from all around the world about the barriers they have faced in conducting and publishing their research.

During these in-depth conversations, scientists shared stories of inadequate funding, language barriers and collaborations with richer nations built on unequal power dynamics. They also outlined the systemic inequalities they faced during the laborious and highly time-consuming process of writing and publishing their work, from biases in peer review to an inability to access relevant literature.

They also told me how biases in academic publishing directly affect scientists careers. For academics, a good record of publications is considered a sign of high performance. Publishing in a respected journal can bring praise and funding, while failing to publish for an extended period of time may be seen as cause for concern.

I also learned how these inequalities harm the broader scientific community.

Low global south representation in climate literature means that the bank of knowledge around climate change and its impacts is skewed towards the interests of scientists from the global north, creating blind spots around the needs of communities in the global south.

Global South Climate Database

After publishing my analysis, I resolved to quote more experts from the global south in my writing, in an attempt to address the geographic biases in my own work.

However, I quickly bumped into a problem. The low publishing rate of academics from the global south often means they have a lower online presence than their counterparts in the global north. This can make it tricky to find relevant experts from the global south to quote in articles – especially when working to tight deadlines.

To tackle this problem, I partnered with the Oxford Climate Journalism Network to launch the Global South Climate Database.

This free database now includes more than 1,000 climate experts from the global south, ranging from scientists to lawyers to policy analysts. Experts on the database collectively speak more than 75 languages, ranging from Spanish to Swahili, as well as all speaking English. And more than 100 countries are represented.

Every one of these experts chose to sign themselves up for the database, indicating that they are keen to be contacted by the media.

The database is also fully searchable. For example, if you type “atmospheric” into the search field, you will find (at the time of writing) 17 profiles, including:

- Prof Shahzad Gani, an assistant professor at IIT Delhi’s centre for atmospheric sciences, in India

- Dr Allison Felix Hughes, a senior lecturer in atmospheric physics from the University of Ghana

- Prof Omar Ramírez, a professor of atmospheric emissions and climate adaptation from Bolivia’s Universidad Militar Nueva Granada

We hope that this database will help elevate the voices of climate experts from the global south in the media. Please use it to connect with brilliant climate experts from all around the world and to bring a fresh new perspective to your work!

This article was written by Ayesha Tandon – the science correspondent at Carbon Brief

Featured photo credit: Amitava Chandra / Climate Visuals