Towards more accessible laboratory practices with Alyssa Paparella

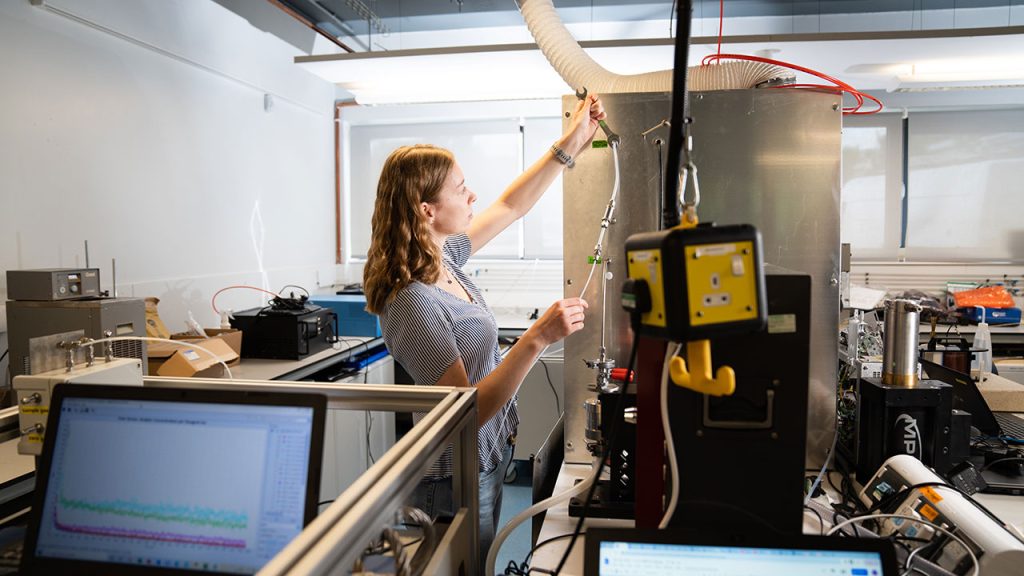

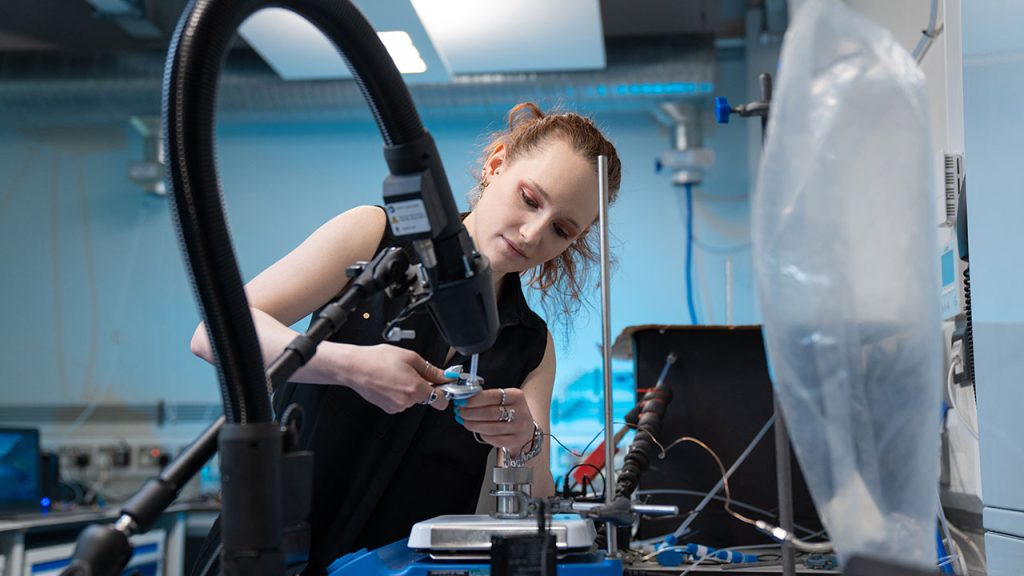

If you close your eyes and picture a typical laboratory, you may be thinking of high bench spaces with conical beakers and laboratory reagents stacked on tall shelves.

However, this laboratory environment is inaccessible for many members of the disability community as it implicitly requires standing for periods of time to carry out work.

Disability is diverse and even within the same diagnosis, different accommodations may be required. But, having high bench spaces is just one of the many barriers that disabled scientists face when working in laboratory spaces.

These types of issues not only create physical barriers, but may also contribute to a culture where people feel unwelcome.

My name is Alyssa Paparella and I’m a PhD Candidate at Baylor College of Medicine. I’d like to set out some of the considerations that can help our research community to make laboratories more accessible and how this will benefit everyone who works in laboratory environments.

As well as running my own experiments in the laboratory, I’m passionate about disability access and inclusion in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM). In March 2020, I created a platform called DisabledInSTEM to raise awareness of disability issues, and build a community for disabled scientists, such as myself.

Disabled individuals are natural problem-solvers. They learn to navigate and adapt to inaccessible spaces. They are well suited to tackling scientific questions through their unique perspective.

However, last year the National Science Foundation’s Women, Minorities, and Persons with Disabilities in Science and Engineering reported that disabled individuals in the US have the highest rate of unemployment out of the demographics investigated. Scientists and engineers with one or more disabilities had an unemployment rate of 5%.

In the UK, research carried out by the Royal Society showed that a higher percentage of students with a known disability are unemployed six months after graduating in science, technology, engineering and maths, than students with no known disability.

One reason that the unemployment rate is high for disabled scientists could be due to inaccessible lab spaces.

To counteract this, I believe we can make laboratory spaces more accessible by learning from universal design principles.

Universal design

Originating from the 1970s by American architect Ronald Mace, universal design refers to striving to make all environments as accessible as possible to everybody, regardless of disability status.

Universal design principles are starting to be discussed in relation to coursework, but need to be expanded to include physical laboratory spaces too.

With universal design, there is a focus on making environments better for all, and this removes the emphasis on disabled individuals having to fight for accommodations.

“Many of the tools that exist in laboratory spaces for disabled individuals will benefit everyone, as they are often more ergonomic, and less demanding on the body.”

Alyssa Paparella, Founder of DisabledInSTEM

Unfortunately, accessible tools are not widely discussed and often need to be sought out, which is why I would like to share some tools that I have found through my experiences that help me in a laboratory setting.

Accessible tools

For those that struggle with fine motor skills, tools such as tube openers may help when conducting experiments that require opening numerous tubes repeatedly. Tube openers help to relieve the pressure on the joints of the hand.

Another simple tool you may consider is a label-maker, which can print out labels for tubes rather than requiring manual writing. Label makers can also help to alleviate the issue of not being able to read someone else’s handwriting, which is to everyone’s benefit.

Because lab-work often requires standing, it could be helpful to invest in anti-fatigue mats. These are specialist floor covers which help take some of the pressure off joints when standing, leading to less fatigue and strain on the body.

There are also electronic pipettes that reduce the need for manually pipetting. And, they can be more accurate than manual pipetting.

You may hear concerns that tools like electronic pipettes are more expensive than typical equipment, but investing in these types of tools is essential to building inclusive laboratory spaces where everyone feels welcome.

Sometimes, disabled scientists who enter into research laboratories may not be aware of how their disability will impact their work, or what adaptations can be made for them.

For this reason, it’s essential that all of us promote the use of accessible tools. Simple adaptations can disabled individuals to focus on science – not on overcoming barriers to disability accommodations.

As well as the physical aspects of a laboratory space, it’s also important to consider the culture of every laboratory workplace – how people behave, and how they think and talk.

Laboratory culture

A welcoming environment will make sure that people do not feel that they have to hide their identity as a disabled individual. It can make a transformational difference to a person’s experience – especially if they are in unfamiliar circumstances, such as working on a field experiment – to know they can ask for extra assistance as they navigate new or different environments.

When an individual does disclose their disability, it should always be treated as confidential. You should not ask intrusive questions, but let the individual lead their conversation to ensure they are comfortable with what’s being shared

Only through a wide-reaching approach, across both physical and cultural barriers, can we make sure that disabled individuals feel welcome in every science and engineering space.

To address the barriers that exist, I believe emphasis needs to be placed on making laboratory spaces accessible through better design, better tools, and by fostering inclusive culture. These changes will open up research for more disabled scientists, and ultimately lead to better science.