What does climate change mean for cold weather?

There was a cold start to the new year, as Arctic air arrived in the UK. The cold conditions prompted questions about the impact of climate change. Why is it so cold when the planet is warming?

We asked climate and weather scientists at the National Centre for Atmospheric Science about “coldwaves”, the role of climate change, and what the UK’s winters will be like in the future.

What is a coldwave?

A coldwave is a period of cold weather, lasting for several days or even weeks, where temperatures are lower than average for that time of year. Like how a heatwave is a period of abnormally hot weather usually lasting several days.

Usually coldwaves are caused by changes to typical air flow, such as shifts to the polar vortex or jet stream, which then allows cold air to move into areas that are usually milder – for example, Arctic or Siberian air flowing to lower latitudes and arriving in the UK.

What does climate change mean for cold weather and UK winters?

Isn’t climate change supposed to make the weather warmer? While global temperatures are rising, local coldwaves and harsh winters are a normal part of our seasons and weather systems. Weather is short term and changeable, so a short period of cold weather does not disprove climate change. In a similar way, climate change does not put an end to all cold weather.

Changes to our climate over longer periods of time could start to play a role in the frequency and intensity of coldwaves. It is clear that climate change is already having a significant impact on heatwaves, so researchers have also been keeping a close eye on the connection between climate change and coldwaves. Cold extremes on most continents will become less intense and less frequent, as stated by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

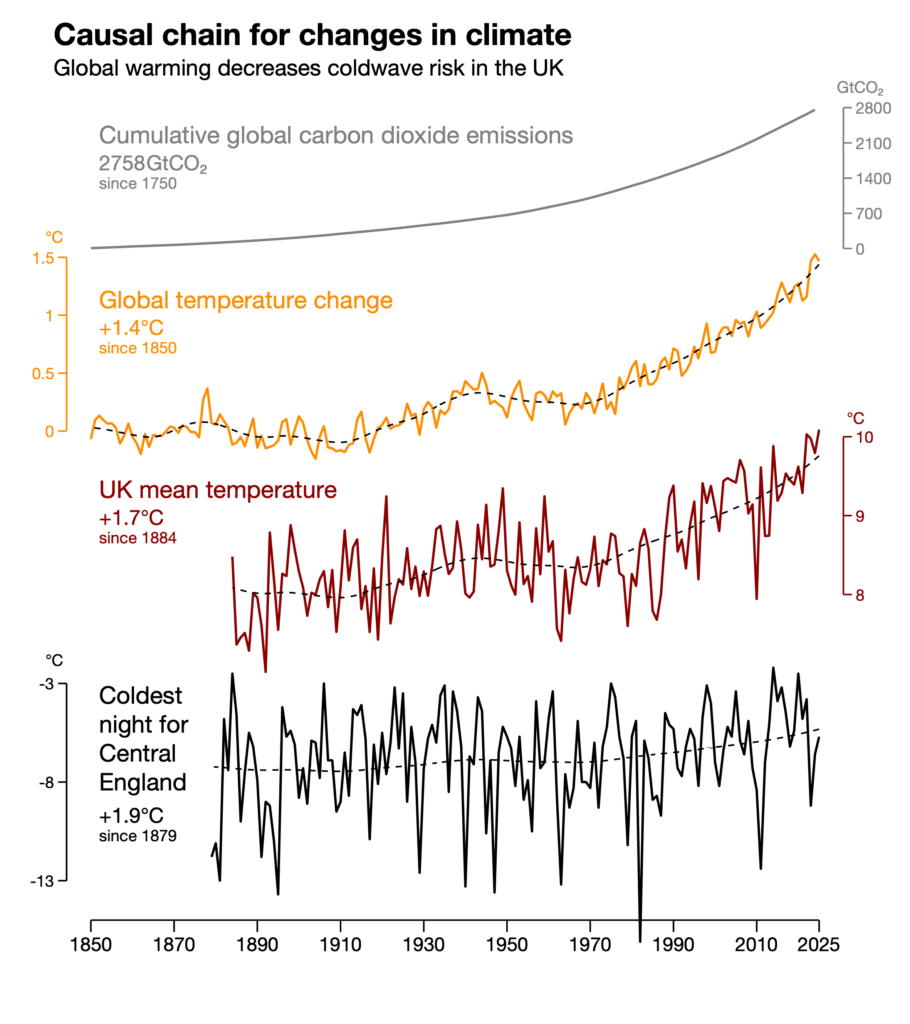

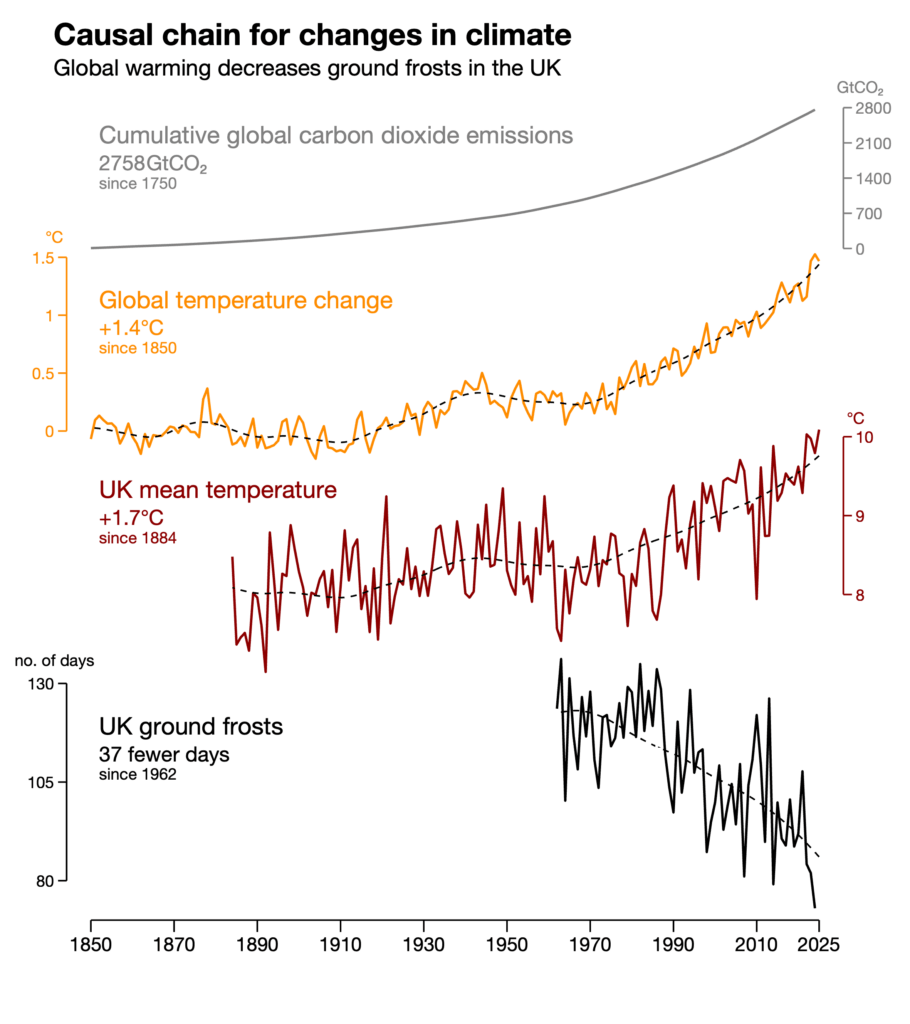

“By visualising weather and climate data alongside each other, we’re able to more clearly see the physically plausible connections between global carbon dioxide emissions, our world’s changing climate, and local weather events here in the UK. These data visualisations show a “causal chain”, which can be a useful tool for communicating about the consequences of climate action and inaction,” outlines Professor Ed Hawkins, climate scientist at the National Centre for Atmospheric Science and University of Reading.

For the UK, it is clear that as global carbon dioxide emissions, global temperature, and UK temperature rise over recent decades, the risk of experiencing coldwaves decreases. Temperatures observed on the coldest nights in the UK between 1879 and 2025, show that the coldest nights have become 1.8°C warmer. As for ground frost days in the UK, there are now 37 fewer a year due to global warming, than compared to 1962.

There are far fewer coldwave days than in the past. I recently found that Europe is experiencing more than five days less of cold events each decade. This reduction is because of global warming effects, which are causing these cold events to be less severe than they were 40 years ago.

In southern Europe, I also find that these coldwaves generally do not last as long as they did previously. So once a coldwave emerges in southern Europe, it does not persist for as long as it used to. Across the whole northern hemisphere, these coldwave events now cover smaller areas than previously.

The impact coldwaves will have in the future, will continue to depend on global warming effects and future emissions.

– Weronika Osmólska, doctoral scientist specialising in extreme cold weather events

Further research is needed to better understand the relationship between climate change and coldwaves, and to develop effective strategies for preparing for and being resilient to these extreme events.

“Children from this generation are experiencing far less snow than previous generations. For many parts of the country, snow is a novelty rather than a regular feature of winter. For society more generally we are not always prepared for snow because it is less frequent, so the impacts can often be larger,” says Professor Ed Hawkins.