Outdoor air pollution in urban areas: scientists inform new parliamentary report

In a report published this week, the Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology (POST) has outlined past and future trends in UK air quality, how pollutants affect our health, and the measures that can mitigate poor air quality.

Dr James Allan, a research scientist at the National Centre for Atmospheric Science and the University of Manchester, who contributed to POST’s recent air quality briefing explains:

“While air pollution in the UK has improved over the decades, it is still currently the single biggest environmental problem affecting human health in the UK. However, as air pollution has changed over the years, so has its characteristics and important sources, so a continual evolution in strategy is needed to deliver continual improvement.”

The new parliamentary report highlights how across the UK, concentrations of air pollutants are uneven – with urban areas typically having poorer air quality, particularly in deprived neighbourhoods.

Particulate matter – natural and human-made microscopic particles suspended in the air – and gases like nitrogen oxides and ozone are the air pollutants causing the most concern for human health in built-up cities, towns and suburbs. Different pollutants are often emitted together and react in the air, creating challenges in attributing health effects to individual pollutants.

The report states that no safe lower limit has been identified for these pollutants, which disproportionately affect vulnerable groups. More vulnerable people include children, people who are older, pregnant, or who have pre-existing medical conditions.

People from socio-economically disadvantaged neighbourhoods and from ethnic minority backgrounds are also more likely to be exposed to poor outdoor air quality where they live, as well as being exposed to higher levels of indoor air pollution. Households in the poorest urban areas produce lower air pollutant emissions and are three times less likely to own a car, but are subjected to higher air pollution levels because of where they are located.

Some urban areas exceed the World Health Organization’s Global Air Quality guidelines for particulate matter and nitrogen oxides, and in recent years air quality has been the subject of infringement proceedings by the European Commission against the UK.

But on the whole, in the majority of urban areas, the concentrations of particulate matter and nitrogen dioxide are declining across the UK. Meanwhile, ozone gas – which at ground level is formed by sunlight-driven reactions between nitrogen oxides and non-methane volatile organic compounds – is slightly increasing.

This Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology briefing note reflects the current state of knowledge regarding the composition, sources, processes and effects of UK air pollution, and what can be done to address it.

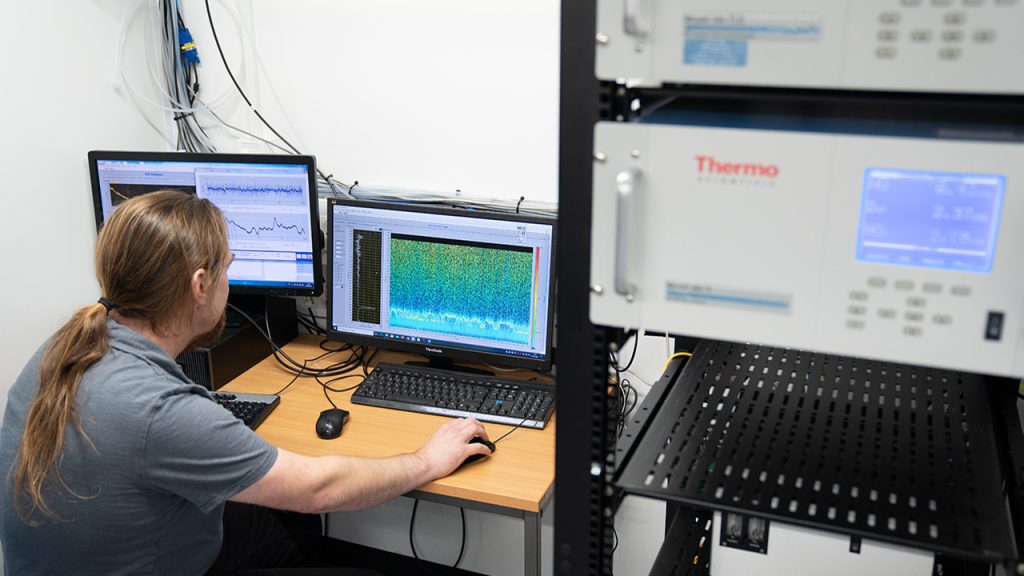

Dr James Allen, a research scientist at the National Centre for Atmospheric Science and the University of Manchester

Urban monitoring sites that track pollutant emissions near their source are located across cities such as London, Birmingham, and Manchester – and are supported by the National Centre for Atmospheric Science and the Integrated Research Observation System for Clean Air (OSCA) project.

Dr James Allan explains: “The detailed evidence acquired by OSCA will support regional authorities to develop made-to-measure air pollution controls, which respond to changing sources of pollution. Urban air quality research like that led by the National Centre for Atmospheric Science will also feed into wider efforts to manage air pollution across the country.”

The UK government is setting two reduction targets for fine particulate matter, also known as PM2.5, to be met by 2040. Modelling forecasts show that most of England has the potential to be compliant by 2030 if sufficient action is taken.

Measures for mitigating poor air quality such as road charging schemes, domestic combustion interventions, tighter standards on industry fuel use, low-emission agricultural technologies, and encouraging less polluting transport modes are being implemented, but the UK’s Chief Medical Officer states that “we can and should go further to reduce air pollution”.

Evidence demonstrating the impacts on health and the effectiveness of these kinds of measures is limited, as it is difficult to define what the interventions are achieving alongside other factors like the weather.

In the near-future, it is expected that as electric vehicle use grows that non-exhaust emissions from tyres, brakes, road wear and road dust will increase. Modelling suggests that despite emissions of non-exhaust emissions, the switch to fully zero emission (at the tailpipe) vehicles by 2035 will improve air quality.

Overall, the UK’s transition to net zero could reduce air pollution in nearly every sector, ranging from transport, home heating to energy production, but the scale of benefits will depend on how replacement low-carbon technologies are used and whether new hazards are managed.

Some actions to deliver net zero could counteract progress being made on air quality through introducing new sources, or increasing emissions of air pollutants, or by changing behaviours.

Researchers from the National Centre for Atmospheric Science are working with government departments to advise, and provide evidence, on the likely positive and negative effects of different net zero pathways on air pollution – not just in urban areas.